Alpine Lessons for Instructors

PSIA AASI

ALPINE: Lesson Progression for Instructors

Master the Mountain

Friday Night Lights

Jr Instructor Program

Teaching Children

CONTENTS:

What makes a great children’s instructor

The CAP Model

Competitive Play

Reflecting on Experiences

Junior Instructor Certificate Program from The Snowpros

Your Responsibility Code

Smart Style Park Code

Alpine Technical Skills

Alpine Fundamentals

Terrain Considerations

Lesson Progressions

References

WHAT MAKES A GREAT CHILDREN’S INSTRUCTOR?

Three key characteristics are adaptability, creativity, and fun. As a children’s instructor, you have to be prepared for anything; no day is the same as the previous. Being adaptable with your lesson content and finding creative ways to deliver it will elevate your teaching and help your students lear. Bring the lesson to life by making it fun relative to the students' stage of development, and you’ll have them coming back for years!

-Chris Rogers

AASI Snowboard Team (2016-24); Vail Resort (CO)

The CAP Model

Cognitive: How Children Think and Perceive

Ages 3-6

Pre-Operational

Beginning language use

Egocentric (Me)

Can only process one thing at a time

Unable to reverse direction

Learns through play and fantasy

Has a short attention span

Examples:

“Look at me!”

Your space is my space

Prefers to tackle one thing at a time

Doesn’t think in concrete concepts

I can get there but not back

Doesn’t know why things are the way they are.

Ages 12-13

Formal-Operational

Abstract thinking is developing

Is starting to visualize

Peer acceptance is important

Overestimates abilities

Examples

Wants to know why things are the way they are and understand why

Can visualize well

Ages 12-13

Formal-Operational

Rapid growth and body changes

Planes of motion start to expand: fore/aft more than lateral/diagonal

Can move body parts independently of another

Teens Plus

Formal-Operational

Uses problem-solving skills

Examples

“I am like others”

Distinguishes fright from wrong

Can think in abstract terms and understand complex concepts

Affective: How Children React, Socialize, Process Emotions, and Communicate

Ages 3-6

Affective: Pre-Conventional

Pre-Operational

May play beside but not with others

Learns through play

Social play with few rules

Slapstick and basic silliness

Morals /Social:

Pleases others to avoid punishment

Thinks good is good and bad is bad

May ask what’s in it for me

May want their mom or dad

May need reassurance

Ages 3-6

Pre-Operational

Body may move as a unit

Uses skeletal bracing

Large muscles develop first

Similar strength between boys and girls

Gross motor skills

Planes of motion - fore/aft

Tire easily

Ages 7-11

Concrete-Operational

Sees the world from multiple points of view

Can process more than one task at a time

Can only process one thing at a time

Appearance vs reality

Starting to judge space, distance, and time

Directional and reversibility

Overestimates abilities

Examples

“Look at us!”

Your space is your space

Thinks about “what if?”

Ready for multiple directions

“I can get there and find my way back”

Wants to know why things are the way they are

Ages 7-11

Affective: Conventional

Concrete-Operational

Cooperative play

Social play with rules

Wants to have fun and play games

SEeks approval

Likes Knock-Knock jokes and toilet talk

Morals/Social:

May think they are as clever as a fox

Seeks consensus

Is developing awareness of others’ feelings

likes to know when they have done something well

Physical: How Children’s Bodies Are Built, How They Grow and Move, and How They Develop Motor Skills and Coordination

Ages 7-11

Concrete-Operational

CoM is moving lower

Strength and coordination might not match

Motor skills developing: gross more than fine/manipulative

Beginning to develop arm and leg independence

Ages 12-13

Affective: Post-Conventional

Formal-Operational

Competition: wants to compare achievements with their peers

Asserting independence

Parody and sarcasm

Morals/Social

Tests authority

Fitting in is important

Self-esteem is important: wants to be treated with respect and does not like to be talked down to

Teens Plus

Affective: Post-conventional

Formal-Operational

Can laugh at themselves

Not keen on competition because they prefer to blend in with peers

Morals/Social

Listens to their conscience

Seeks peer acceptance

Understands universal ethics

Teens Plus

Formal-Operational

Growing into adult body

WHAT MAKES A GREAT CHILDREN’S INSTRUCTOR?

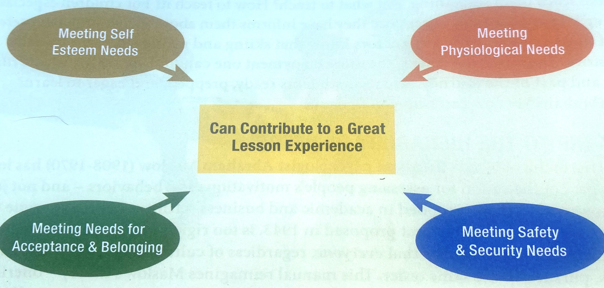

As snowsports instructors, our role for the time we are with our students is to make their day. make them smile, laugh, and feel accomplished. Gaining insight into who our students are as individuals with thoughts, concerns, fears, goals, and interests, the great coach respects all these factors when planning out the day, weekend, or season. A great coach not only elevates the skill level of each student but also leaves the child feeling accomplished and fulfilled.

— Sue Kramer

PSIA-AASI National Children’s Task Force; Eastern Division Advanced Children’s Educator Team; Bromley Mountain, VT

Competitive Play (ages 7 to 11 years)

In this age group, children become more interested in results as well as participation. Rules take on more importance, and competition may become more interesting. Although these kids will keep score, losing could cause some to become demoralized. De-emphasize the importance of winning by having all competitors try to do their best or even to beat their previous best performance. Shift from that of beating someone else to pushing previous limits or bettering past performance. Examples:

How many turns can you make on one ski?

How far can you ride in this steep bump line before you need to rest (or to regain control)?

Let’s time the next run and see who can get to the finish line closest to 40 seconds (in other words, you’re not rewarding the fastest; you’re rewarding the most accurate).

How may medium-radius turns does everyone think it will take to get from here to that pine tree?

WHAT MAKES A GREAT CHILDREN’S INSTRUCTOR?

To me, these three things are key:

Self-awareness. It’s helpful to be aware of how you and your words are being received. Children are often quite literal - and so honest! They will let you know in both subtle and obvious ways if you are connecting with them. “Where are we going next?" translates to “Let’s move already, enough standing and talking!”

Energy. Be energetic, enthusiastic, and exciting. Match a child’s energy level (boost it if necessary), share your enthusiasm for skiing/riding, and create and exciting learning session.

Attitude. Choose a relatable attitude. Be the instructor/coach that your inner child would want to spend time with. Know the difference between a 4-year-old and an 8-year-old… really know the difference! Honor a child’s age and life experience.

—Stacey Garrish

Training Manager, Beaver Creek Ski and Snowboard School (CO)

WHAT MAKES A GREAT INSTRUCTOR

A great children’s teacher is one who can listen and build a strong connection with their students through communication. One who is engaging, FFUN, and can show empathy when needed. Most of all, this person has patience and the ability to connect with children and ignite their love for snowsports.

—Nicholas Herrin

PSIA-AASI CEO; PSIA Alpine Team member (2004-2016)

Reflecting on Experiences

It’s not enough just to have information presented and to perceive it through the senses. Kolb builds on the theories around learning preferences to assert that every learner needs to go through a process in order to turn information into knowledge. To Kolb, “Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience.”

In other words, in what’s known as experiential learning, you don’t just learn through experiences; you have to reflect on those experiences to truly internalize them. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle, asserts that learning occurs through a four-step process:

Concrete Experience - Learners have a concrete experience

Reflective Observation - Learners observe and reflect on that experience

Abstract Conceptualization - Learners form abstract concepts (analysis) and generalizations (conclusions) based on observations and reflections

Active Experimentation - Learners test a hypothesis in future situations, which result in new experiences.

Junior Instructor Program from the Snowpros

The Snowpros offer a free course for new instructors that can be found here: lms.thesnowpros.org/product/new-instructor-course/. This is a free course for people thinking about, or just getting started in, teaching snowsports.

A Member School Toolkit PDF for the Junior Instructor Program can be found here: https://thesnowpros.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Junior-Instructor-Toolkit-for-PSIA-AASI-Member-Schools-FINAL-1-compressed-1.pdf

Check back (currently closed) for the Junior Instructor Certificate Program offered by The Snowpros: https://lms.thesnowpros.org/courses/junior-instructor-certificate-program/. The is a course that requires enrollment.

YOUR RESPONSIBILITY CODE

Always stay in control. You must be able to stop or avoid people or objects.

People ahead or downhill of you have the right-of-way. You must avoid them.

Stop only where you are visible from above and do not restrict traffic.

Look uphill and avoid others before starting downhill or entering a trail.

You must prevent runaway equipment.

Read and obey all signs, warnings, and hazard markings.

Keep off closed trails and out of closed areas.

You must know how and be able to load, ride and unload lifts safely. If you need assistance, ask the lift attendant.

Do not use lifts or terrain when impaired by alcohol or drugs.

If you are involved in a collision or incident, share your contact information with each other and a ski area employee.

Winter sports involve risk of serious injury or death.. Your knowledge, decisions, and actions contribute to your safety and that of others.

If you need help understanding the Code, please ask any ski area employee.

SMART STYLE PARK CODE

Start Small – Work your way up. Build your skills.

Make A Plan – Every feature. Every time.

Always Look – Before you drop.

Respect – The features and other users.

Take It Easy – Know your limits. Land on your feet.

Alpine Technical Skills

In skiing, a person must maintain equilibrium between the forces that act on them and the forces that act on the skis.

Rotary: The ability of the skier to control the direction of the ski’s point.

Left

Right

Straight

Edging: The ability to tip a ski on edge and adjust the angle between the base of the ski and the snow.

Pressure: The ability to control pressure from the ski’s tip to its tail.

Pressure: The ability to distribute pressure from one ski to the other.

Pressure: The ability to control the overall magnitude of pressure acting on the base and or edge of the skis.

Alpine Fundamentals

Control the relationship of the center of mass (CoM) to the base of support to direct pressure along the length of the skis.

Control pressure from ski to ski and direct pressure to the outside ski.

Control edge angles through a combination of inclination and angulation.

Control the skis’ rotation with leg rotation, under a stable upper body.

Regulate the magnitude of pressure created through ski snow interaction.

Consider how these fundamentals relate to the technical skills of pressure, edging and rotary.

TERRAIN CONSIDERATIONS

Like all ski areas, Crystal offers unique terrain for teaching Alpine skiing. The following locations are best suited for teaching purposes, noting that surface condition, weather, and customer traffic make their respective use subject to change.

Instructors should always be aware of the fall line and intersections.

Alpine Progressions

WALKING IN ALPINE EQUIPMENT

Designed for the efficient and safe transfer of energy, alpine ski boots make walking awkward for first-time participants. Alpine ski boots limit the ankle's ability to articulate and limit the sensations associated with normal footwear.

Explain the rigidity of the boots and why it is needed for alpine skiing.

Explain the important sensations the student may feel in ski boots, paying particular attention to the tongue-shin connection and how it relates to the compression and decompression of the arch.

Spend a brief time walking in ski boots, which may include following the leader task. This allows the student to become accustomed to limited ankle articulation and identify boot fit issues.

Walking with skis on presents three challenges foreign to first-time participants:

Having a locked-down heel.

The sliding sensation.

The length of the skis.

Spend a brief time working from a tall stance to a short stance; this may include small leaper tasks. Walk up a gentle grade sideways and in a herringbone to experience the movement patterns required. Ask students to share their feelings, allowing them to reflect on their sensations. There will be many different answers.

Scooters (one ski on) will help students get used to the glide involved with ski-snow contact.

Incorporate flat terrain.

Start with shuffles.

Work up to a walk to a glide. This will encourage balance through experiential learning.

Take note of excessive upper body movements.

Ask students what they feel.

Star turns allow students an opportunity to get used to the length of their skis. They must be performed in flat terrain.

Star turns stepping around 360º.

Star turns with tip in the center.

Star turns with tails in the center.

Ask students what they feel.

Extra Credit: Stepping laterally up hill and with a herringbone.

GETTING UP AFTER FALLING

Take a ski off.

When putting it back on, be sure to have it on the uphill side with both skis perpendicular to the fall line.

Make sure the binding heel lever is disengaged, in the down position.

Check for snow in the bindings and or on the boot soles.

On Steeper pitches, you can also position the skis downhill from you, perpendicular to the fall line, and push yourself up by moving towards the tips of the skis.

THE WEDGE PROGRESSION

The Wedge progression is time-tested and covers the widest range of participant skill sets.. Note: If a participant demonstrates an ability to perform direct to parallel as a beginner, provide them with turn shape tasks. It is still recommended to incorporate a braking wedge to control speed in lift lines.

The Wedge progression provides the safest learning outline where there is limited run-out and populated learning areas.

The wedge allows the participant to concentrate on fewer skills (Rotary) and fundamentals (Control the ski’s rotation with leg rotation, under a stable upper body, and control the relationship of the COM to the base of support to direct pressure along the length of the skis).

Simply put, the wedge is ski tips together and ski tails apart. Speed is controlled by regulating the size of the wedge; the larger the wedge, the slower the skier will go. The size of the wedge can also be viewed through stance height. The taller the skier, the narrower the wedge is, or vice versa. The rotation of the upper legs in an inward direction generates the movements needed to create a wedge.

Introduce the wedge statically in a flat area. Demonstrations should be level-appropriate.

Skis can be slid into the wedge, stepped into the wedge, or hopped into the wedge.

Emphasize a moderately athletic stance that distributes the participant's COM over the length of the skis.

Key flex points will utilize the hip joint, the knee joint, and the ankle joint. Key sensations include pressure on the tongue of the boot.

Move to a low grade and perform a straight run to a gradual wedge stop. Demonstrations should be level-appropriate.

Use the skier’s stance height as a visual indicator.

Use the increase and decrease of pressure on the tongues of boots as a kinesthetic indicator.

Introduce the wedge turn as a means of redirecting the skis and an alternative way to stop.

Demonstrations should be level-appropriate.

Emphasize leg rotation in shorter radius turns. The head may turn in preparation for the upcoming turn.

Use the increase and decrease of pressure on the tongues of the boots as a kinesthetic indicator.

THE WEDGE PROGRESSION: TROUBLESHOOTING

Participant cannot make a wedge: increase the size of their wedge or redirect the skis.

Weight is distributed to the back of the skis (heels). People naturally assume a plumb stance when walking downstairs or slopes as opposed to being perpendicular to the slope. People tend to move their COM as their feet slide forward.

Correctly perform a demonstration that allows participants to view you from the side.

Incorporate tasks within vertical planes, such as high/low stance, hopping, and jumping. “Remember, knees are over the toes.”

Reiterate flex in the joints and pressure against the tongue of the boot. Think alternatively, “Can you pull your feet behind your Hips?”

Weight is distributed more on one ski than the other. Everyone has a stronger side. It is a natural reaction to lean to the safer, stronger side.

Correctly perform a demonstration that allows participants to view you from the front and back.

Incorporate tasks that encourage level shoulders and a level pelvis.

Relate movements that facilitate equal pressure on both skis.

Note: In all cases, props such as the Ski Ring or hula hoop may be incorporated.

THE WEDGE PROGRESSION - TURNING

In a flat area, practice the following after demonstrating:

Balancing on one ski, then the other, with skis in a straight position. This can be done keeping the ski that is being picked up parallel to the snow surface, and/or with the tip down and tail up. Ask the participants what they felt regarding body awareness.

From a small wedge position, balance on one ski, then the other. This can be done keeping the ski that is being picked up parallel to the snow surface, and/or with the tip down and tail up. Ask the participants what they felt regarding body awareness.

On a low-grade pitch practice the following after demonstrating utilizing smaller radius turns. (Note: When we walk, we lead with a weighted inside foot to turn. Effective alpine skiing requires a weighted outside ski.)

Brush the tail of one ski out and apply a little more weight to it. This may involve tipping the pelvis and shoulders slightly towards the brushed ski side.

Apply more weight to one ski. This may involve tipping the pelvis and shoulders slightly towards the pressured ski side.

Increase the radius of the turns to introduce speed control.

Stalling will occur for a variety of reasons, which include tactics. Encourage and demonstrate turn shapes that flow, as well as adjustments in stance height: tall in the initiation, gradually shortened through shaping to finish.

THE WEDGE PROGRESSION - MATCHING

In a flat area, demonstrate and practice matching skis. The uphill ski can be picked up and our slid parallel to the downhill ski, which encourages the distribution of weight from one ski to the other. Additional rotational skill sensations occur via the leg rotation required when moving the uphill ski into a parallel position. Note: This can be done with boot work.

Demonstrate and practice the same task moving across the hill. Encourage slight tipping of the pelvis to weight the downhill ski and take weight off the uphill ski.

From a wedge position, guide the inside ski into a parallel position as the skis cross the fall line. This may involve tipping the pelvis and shoulders slightly towards the outside ski.

Increase the radius of the turns to introduce speed control.

Introduce the pole swing as a means of timing, and or moving the COM forward.

Stalling will occur for a variety of reasons, which include tactics. Encourage and demonstrate turn shapes that flow, as well as adjustments in stance height. Tall in the initiation, gradually shortened through shaping to finish.

THE WEDGE PROGRESSION TROUBLE SHOOTING

Troubleshooting: the participant cannot match the skis because:

Knees are locked together.

Participant is using their torso to redirect their skis as opposed to their lower body.

Weight is distributed to the back of the skis (heels). People naturally assume a plumb stance when walking downstairs or slopes as opposed to being perpendicular to the slope. People tend to move their COM as their feet slide forward.

Correctly perform a demonstration that allows participants to view you from the side.

- Incorporate tasks within vertical planes, such as high/low stance, hopping, and jumping. “Remember, knees are over the toes.”

Reiterate flex in the joints and pressure against the tongue of the boot. Think alternatively, “Can you pull your feet behind your Hips?”

Troubleshooting: Weight is distributed more on one ski than the other. Everyone has a stronger side. It is a natural reaction to lean toward the safer, stronger side.

Correctly perform a demonstration that allows participants to view you from the front and back.

Incorporate tasks that encourage level shoulders and a level pelvis.

Relate movements that facilitate equal pressure on both skis.

BASIC PARALLEL - MATCHING SKIS THROUGHOUT THE TURNING PHASE

In a flat area, demonstrate and practice matching skis through the tipping of skis on and off edges. The uphill ski can be picked up to encourage the distribution of weight from one ski to the other. Incorporate the sensation of compressing and decompressing the foot arches. Ask for feedback regarding rotational skill and pressure skill sensations. Note: This can also be done with Boot work.

Demonstrate and practice the same task moving across the hill. Encourage a slight tipping of the pelvis to weight the downhill ski and take weight off the uphill ski. The uphill ski should be slightly ahead of the downhill ski.

Demonstrate and practice “J” turns, concentrating and encouraging a slight tipping of the pelvis and shoulders from the outside ski to neutral to the other outside ski.

Demonstrate and practice turns shapes, concentrating on the skier's height adjustments throughout the turning phase.

ncrease the radius of the turns to introduce speed control.

Introduce the pole swing as a means of timing, and or moving the COM forward.

Stalling will occur for a variety of reasons, which include tactics. Encourage and demonstrate turn shapes that flow, as well as adjustments in stance height finish.

Food for thought: Constantly moving vision ahead. Feeling the snow ski base interaction. Breathing in at the beginning of the turn and breathing out in the finish phase. incorporating the gluteus maximus and latissimus dorsi. Focus on the position of the pelvis (tip, tilt, and rotate). Dorsiflexion of the ankle. Refining the pole swing. Stepping while skiing. Shuffling while skiing. Hopping while skiing.

BASIC PARALLEL TROUBLESHOOTING

Participant cannot match skis because:

Participant is using their torso to redirect their skis as opposed to their lower body.

Weight is distributed to the back of the skis (heels). People naturally assume a plumb stance when walking downstairs or slopes as opposed to being perpendicular to the slope. People tend to move their COM as their feet slide forward.

Correctly perform a demonstration that allows participants to view you from the side.

Incorporate tasks within vertical planes, such as high/low stance, hopping, and jumping. “Remember, knees are over the toes.”

Reiterate flex in the joints and pressure against the tongue of the boot. Think alternatively, “Can you pull your feet behind your Hips?”

Weight is distributed more on one ski than the other. Everyone has a stronger side. It is a natural reaction to lean to the safer, stronger side.

Correctly perform a demonstration that allows participants to view you from the front and back.

Incorporate tasks that encourage level shoulders and a level pelvis.

Relate movements that facilitate equal pressure on both skis.

INTERMEDIATE PARALLEL TASKS

Demonstrate & practice the following to promote flexion in the pelvis, knees, and ankles. (Bent at the waist, while feeling forward, places the COM aft).

Pressure on the tongues of the boots.

Picking up a ski while turning on easy terrain. Tip on the snow, tail in the air.

Cover toes with knees.

Small to large hops focusing on the sound of the landing.

Focus on breathing in at the beginning of each turn and how it effects the position of the pelvis

Elbows in front of the rib cage (pole swing work will help).

Visual line of site needs to be increased.

Utilizing a prop.

Control the relationship of the center of mass (COM) to the base of support to direct pressure along the length of the skis.

Are the tips of the skis bouncing? (Indicates the skier’s COM is aft.)

Is the skier control in the finish phase? (Indicates the skier’s COM is aft, specifically in the finish phase.)

Demonstrate & practice the following: Promote commitment to the new outside ski.

Hockey stops (soft or hard).

Soft hockey stops to a turn.

Skiing across the hill and picking up downhill ski. Try leaving the tip on the snow and picking up the tail (Note: it may be set down when crossing).

Shuffle turns.

1000 steps.

Hops in the transition, landing on both skis evenly.

Control edge angles through a combination of inclination and angulation.

Does the skier make a “Z” shaped turn? (This may indicate a delayed edging movement).

Does the skier wash out through the finishing phase of a turn? (This may indicate edging movements that begin too early, or may be the result of banking?).

Demonstrate & practice the following: Create an angle that facilitates a consistent-edged track through the shaping phase of the turn. (Note: different conditions, desired outcomes, and turn shapes require different degrees of edge angle duration and timing.)

Half circles exploring the margins. Start with instep pressure (ankle) to knee angulation to pelvis angulation/inclination to spine inclination (Ask the participant what they felt about their stance height).

Half circles within a javelin position (Ask the participant what they felt about their stance height).

Railroad turns on lower pitches (Ask the participant what they felt about their stance height).

Figure eight skating drills.

Hockey stops.

Pivot slips.

The teapot drill (Ask the participant what they felt about their stance height).

Explore pole position and pole swing.

Control the ski’s rotation with leg rotation, under a stable upper body (Note: The torso and legs connect in the hip socket).

• Are the skis washing out in the shaping phase and finish phase of the turn? (Visual indicator will be the displacement of snow).

• Is there a delay in the ski's redirection in the initiation phase of the turn? (Visual indicator will be exaggerated upper body rotation, followed by

a delayed redirection of the skis

Demonstrate and practice the following: Incorporate effective rotary movements required for the desired ski direction.

With one ski on, draw an arch with the boot that goes from the back of the binding to the front of the binding.

Promote steering the boot as opposed to pivoting the boot. Ask the participant what they felt.

Hockey stops.

Hockey stops to a turn and back without interrupting the turn flow.

Pivot slips.

Use the zipper of the participant's coat as a visual indicator (Note: If the zipper of the coat faces downhill the whole time, it will be ineffective).

Moderate crab walks on lower pitches.

Draw a line down the fall-line and have the student focus on the line while performing short to medium radius turns.

Ask participants what they felt in the hip socket, core, and upper legs while performing tasks.

Regulate the magnitude of pressure created through ski snow interaction.

Does the skier face challenges when the terrain and conditions change?

Does the skier face challenges when turn shapes change?

Demonstrate & practice the following: Incorporate tasks on different yet safe terrain and conditions. Continually ask for feedback.

Perform different turn shapes in one run. Continually ask for feedback.

Follow the leader, take turns being the leader.

Give a task, such as three medium radius turns, three short radius turns, etc.

REFERENCES

Professional Ski Instructors of America-American Association of Snowboard Instructors (2014). Alpine Technical Manual. American Snowsports Education Association, Inc.

Professional Ski Instructors of America-American Association of Snowboard Instructors (2021). Teaching Children Snowsports Manual. American Snowsports Education Association, Inc.

PSIA-AASI-C

PSIA-AASI- NW